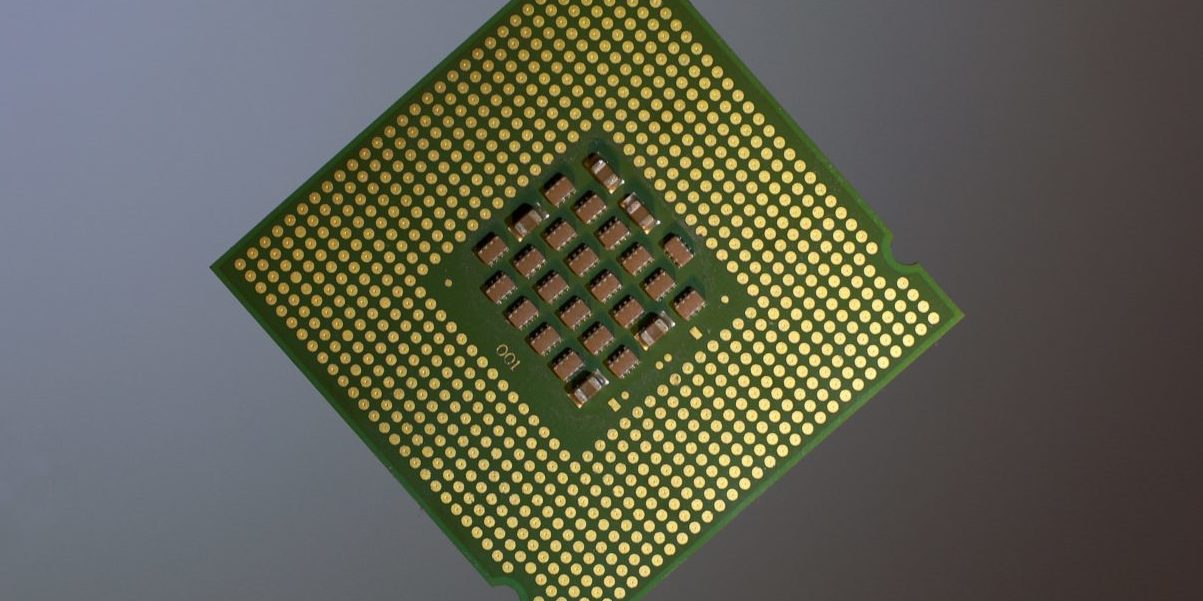

Beginning in 2020 and accelerating into 2021, a chip shortage has, to various extents, plagued the estimated 169 industries which depend upon them. While a small number of firms stockpiled chips in anticipation of just such an occurrence, the overwhelming majority of firms for which semiconductors are a key factor input have had to reduce their output.

As lockdowns and indoor occupancy limits were imposed with the spread of Covid-19, many semiconductor manufacturing facilities came to be operated with skeleton crews at lower capacity. The already tariff-slowed pace of chip production began to decline more precipitously.

Peter C earle – AIER

Early in 2020, predicting that the spread of a respiratory virus would lead to a scarcity of inputs that constitute the very backbone of all modern technology would have sounded ludicrous. But amid a hotchpotch of non-pharmaceutical state interventions, geopolitical wrangling, income redistribution, sudden shifts in work patterns, and the knock-on effects of those, that has occurred and persists.

No one, and certainly not I, can accurately forecast when, where, or how the current array of price distortions and shortages will normalize. An appreciation of the sophistication of modern commerce requires recognizing the ease with which the commonplace can be derailed by seemingly innocuous policies. And relatedly, the tendency for secondary and tertiary effects of political miscalculation to unexpectedly bubble up in odd corners and folds of the economy.

Source: The Great Semiconductor Shortage

See also

BBC: UK food supply chain vulnerable to cyber-attack